Introduction

My work this summer can, in many ways, be summarized by this insightful quote by climate activist Naomi Klein:

“Part of our work now – a key part – is not just resistance, not just saying ‘no.’ We have to do that, of course, but we also have to fiercely protect some space to dream and plan for a better world.” – Naomi Klein, No Is Not Enough

From our country’s ongoing reliance on fossil fuels to its staggering decline in metrics of civic health and engagement, there are many things to say “no” to in America today. What we’re not good at is saying “yes.”

According to political scientists Donald Kinder and Nathan Kalmoe, Americans may have more in common with each other than our vitriolic Facebook feeds would suggest. Building from Philip Converse’s groundbreaking work on belief systems, they argue that ideological differences stem more from “the attachments and antagonisms of group life” than true ideological alignment. In other words, people back particular ideologies because doing so is acceptable in the context of their social spheres.

So I wonder, how might we reframe conversations about the future in a way that is not easily pigeonholed as liberal or conservative? Could doing so enable a more genuine and productive exchange of ideas between people who would otherwise consider each other ideological enemies?

Kalmoe and Kinder’s ideas are echoed by Kathy Cramer’s work on group-based biases in rural Wisconsin. In fact, Cramer’s 2016 book The Politics of Resentment played a crucial role in inspiring me to return to my hometown in central Wisconsin for my thesis research in Comparative Media Studies. In my case, I’m seeking the exceptions to her popular (and often accurate) portrayal of the disenchanted rural Wisconsinite to understand how my expertise in media and game design can support the handful of activists working to engage their neighbors addressing both local and global challenges in these communities.

Most of this research takes the form of semi-structured interviews with activists, residents, and community managers, but I’m also running a few experiments… somewhat “out-there” experiments, you might say. These experiments are designed less as solutions than as ways to test various assumptions about engaging people with local civics and activism.

In this post, I’m excited to share the first of these experiments: The Community Futures Game. Located at the Appleton Public Library – the primary library serving the city’s 70,000 residents – this experience invites passersby to co-create future-oriented narratives for their communities. (In retrospect, the project is less narrative-focused that I’d hoped it would be, but it’s only a first iteration.)

The goal of this project is to create a fun experience that encourages players to think creatively about the distant future in a frame that ignores the traditional liberal/conservative binary. My hypothesis is that asking people to imagine what their community could be like in 100 or 1000 years will enable them to imagine a world beyond group-based ideologies.

Designing the Community Futures Game

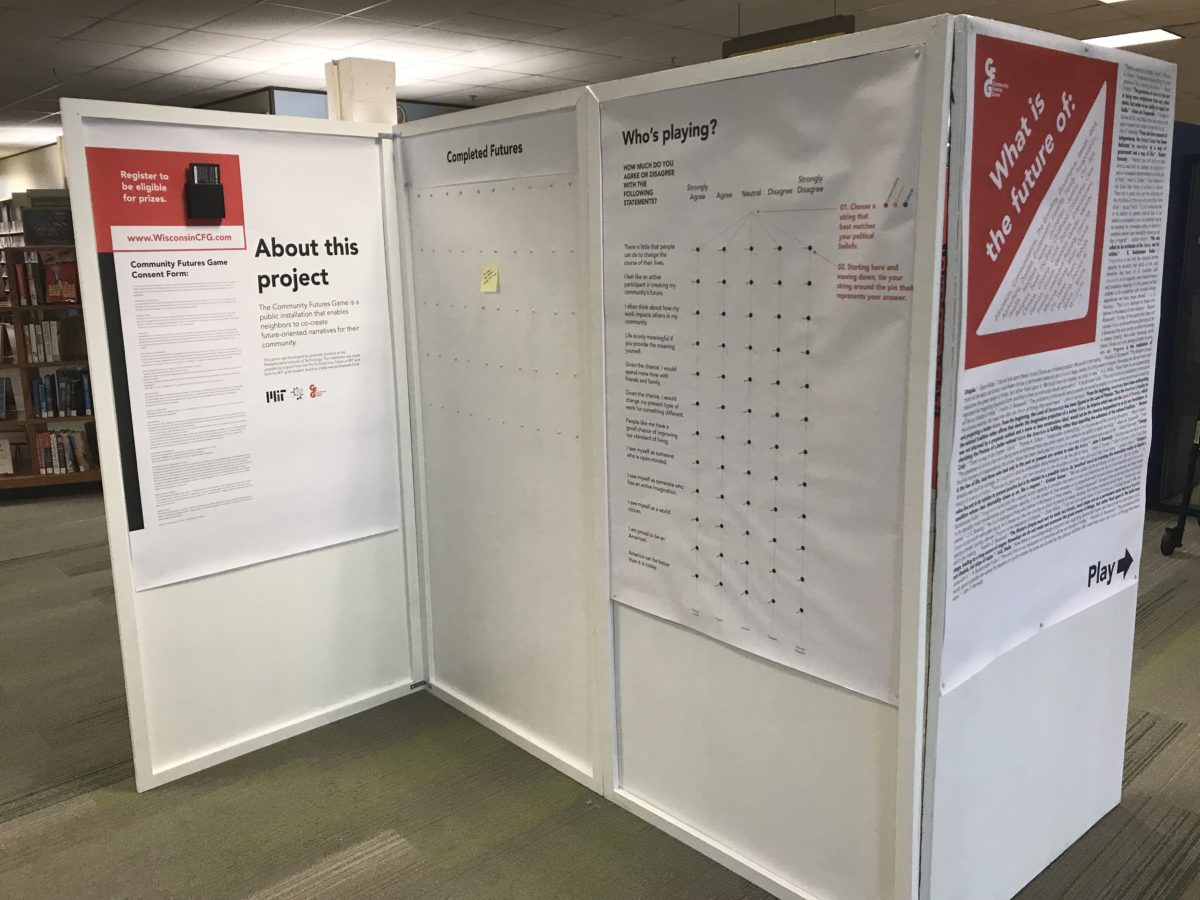

The design of the Community Futures Game began in Professor Mikael Jakobsson’s spring course entitled “Playful Social Interaction Design Explorations” (yes, it’s a mouthful!). The game was originally a table-top game (described here) which was reimagined as public installation earlier this summer. The current exhibit at the Appleton Public Library is the first-iteration prototype of this format. It consists of the following elements:

Title Panel:

The title panel draws attention to the game and is intended to introduce the spirit of play. With quotes from famous Americans (and a few others) throughout history, it focuses on the idea that the United States was founded on the promise of constant innovation and improvement. As Herbert Croly put it in 1909:

“An America which was not the Land of Promise, which was not informed by a prophetic outlook and a more or less constructive ideal, would not be the America bequeathed to us by our forefathers. In cherishing the Promise of a better national future the American is fulfilling rather than imperiling the substance of the national tradition.”

Community Futures Game title panel

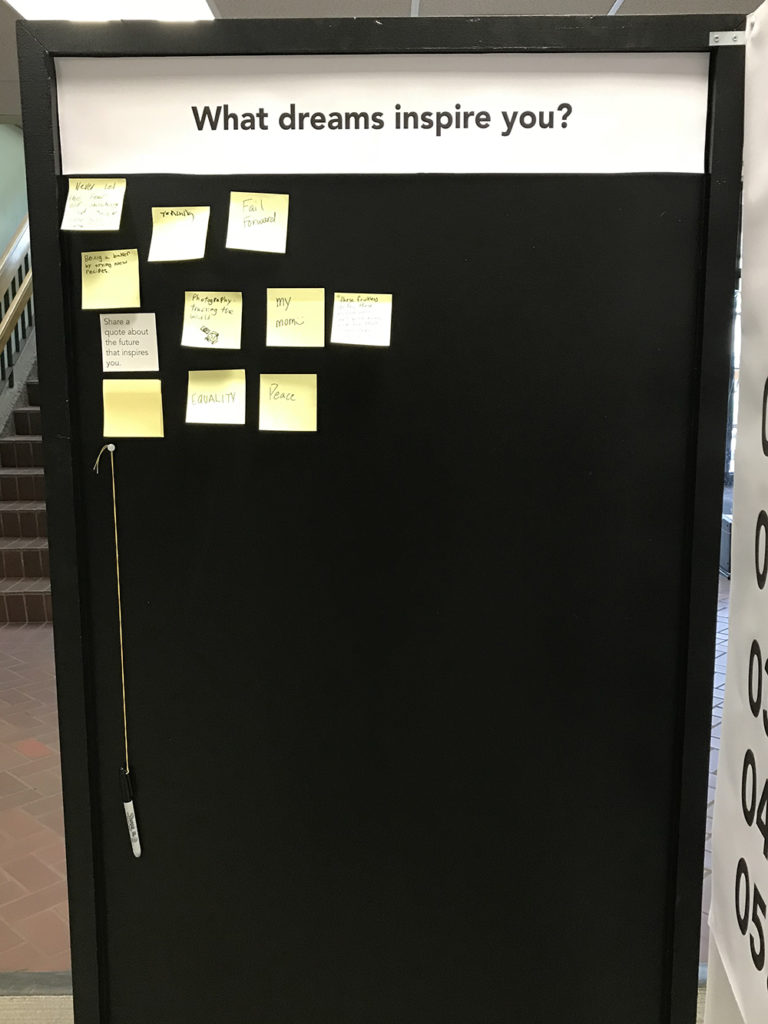

Sticky Panel:

When you follow the game around to the right you encounter the sticky note panel. This is largely a placeholder for future ideas in later iterations. It currently invites participants to share their own favorite quotes about the future.

Game Instructions A:

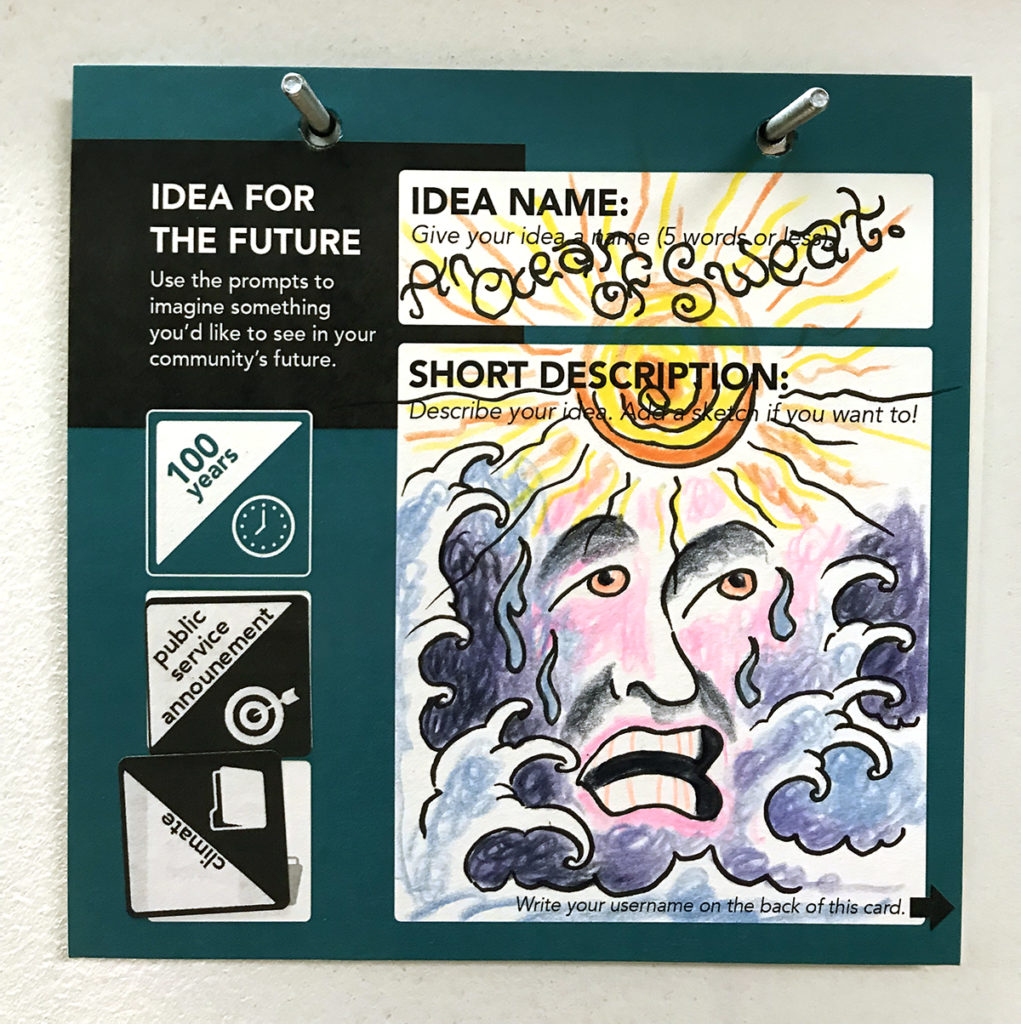

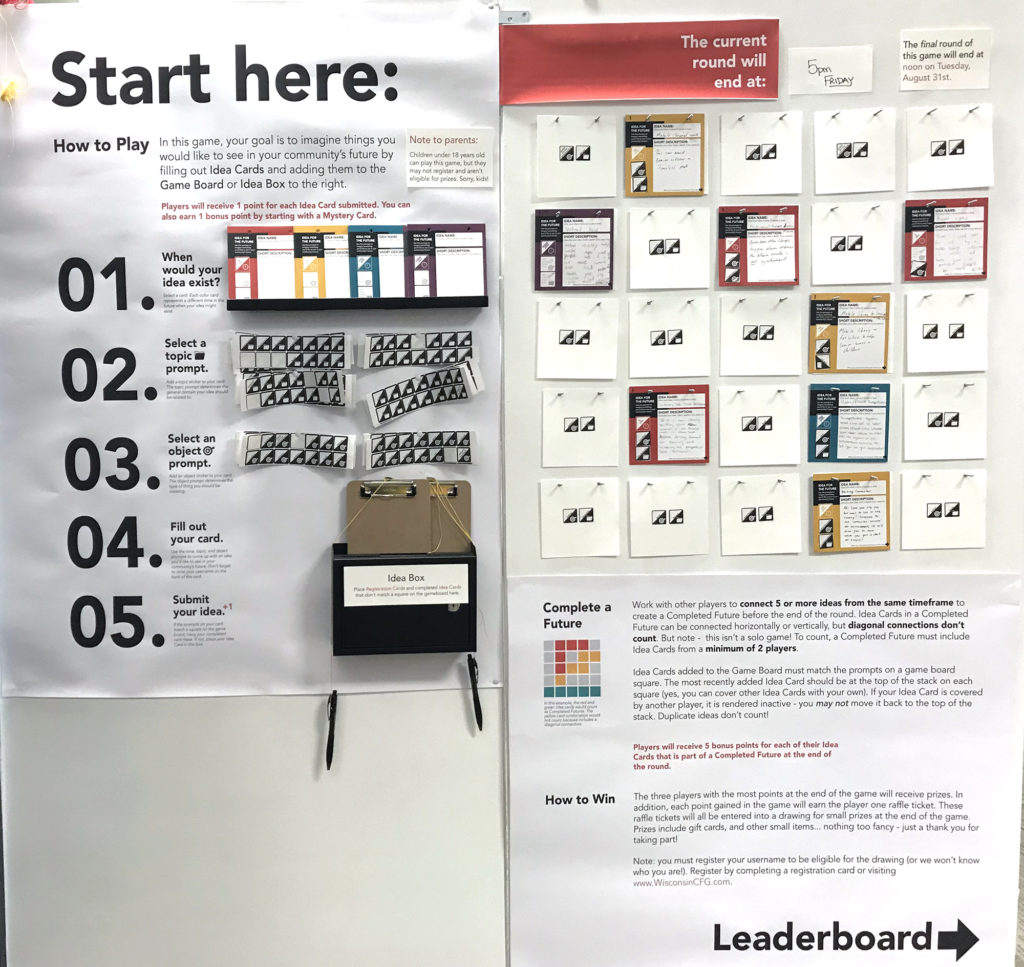

The first panel of the game itself provides step-by-step instructions for completing an Idea Card – the core element of the Community Futures Game. This includes blank idea cards from four “timeframes” – 1, 10, 100, and 1000 years – as well as object stickers, topic stickers, and the Idea Box.

Game Instructions panels

Game Instructions B:

The second panel of the game includes the game board and instructions for how to win.

Leaderboard Panel:

The leaderboard panel includes – a leaderboard! This is updated manually at the end of each round of the game. It also includes instructions for registering to play the game.

About Panel:

This panel provides background information on the project and its funders. It also includes a second set of instructions for registering to play the game and the full text of the subject consent form registered with MIT IRB. The consent form was placed on this panel because it is the second-most-visible panel from the front of the exhibit.

Completed Futures Panel:

When players succeed in connecting five ideas from the same timeframe on the game board, a “Completed Future” is created. Completed Futures are displayed here throughout the duration of the game.

String Board:

The string board consists of 20 questions which can be answered by tying a string around a nail representing your response, one by one. The colors of the string represent the player’s political ideology.

As you can see, this experience actually consists of several tests that could be remixed into future experiences based on their performance in this first test.

The Build

The various elements of the Community Futures Game installation were designed in Adobe Illustrator and mocked up in Sketchup Models.

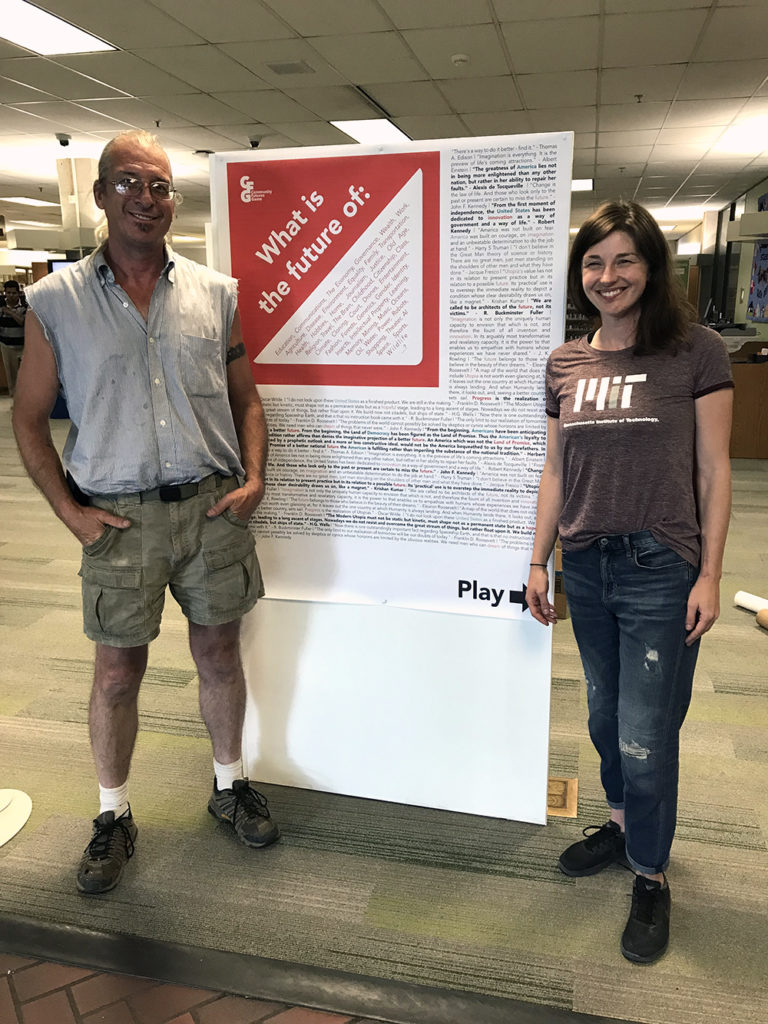

The frame is constructed of ¼” panelboard, 1’x2’ frames, and metal brackets to hold the panels together. The content was printed on 3’x4’ posters and taped and tacked to the frame on site. Huge thanks go to my dad, the amazing Brian Falck, for contributing tools, time, and expertise to the construction and setup of the installation frame.

Installation of the exhibit took about five hours on site at the Appleton Public Library. This lengthy setup time was largely due to the late arrival of prints which had to be cut and prepared on site, instead of in advance. I expect future setups to take closer to two hours to complete.

Me and my dad, Brian Falck, whose guidance made this project infinitely better (and more fun).

Results

Coming Soon!